Charles Nicola Koshen, the first biographer of Chardin, claims that the artist realized his calling on the day when he saw and tried to write a carcass of a rabbit. On this day, the biographer believes, Chardin realized that the still life attracts him much more than the allegorical scenes with the gods and heroes.

“Before that, he never wrote fur,” says Koshen, “and now he realized that you do not need to write fur behind a hair and try to reproduce small details, instead you need to convey all the fur as accurately as a single mass.” Since then, the broken game often appeared in the still lifes of Chardin.

He wrote it enthusiastically and simply, not at all trying to decorate, which distinguished most French still lifes of the XVIII century. His “Still Life with a Hare” is the most poetic and at the same time an artless hymn to cooks, hunters, and also to the battered hare.

An animal carcass hangs against the backdrop of a stone wall. Near the muzzle – a few drops of blood. In a different way, but with no less taste, the later “Still Life with a Duck”, 1764, is written. The dazzling white feathers of a duck seem to glow on a gray background. This feeling is enhanced by a snow-white napkin, reminiscent of the lifeless bird’s wing that hangs.

Prayer before dinner by Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin

Prayer before dinner by Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin Scat by Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin

Scat by Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin Bodegón con una liebre – Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin

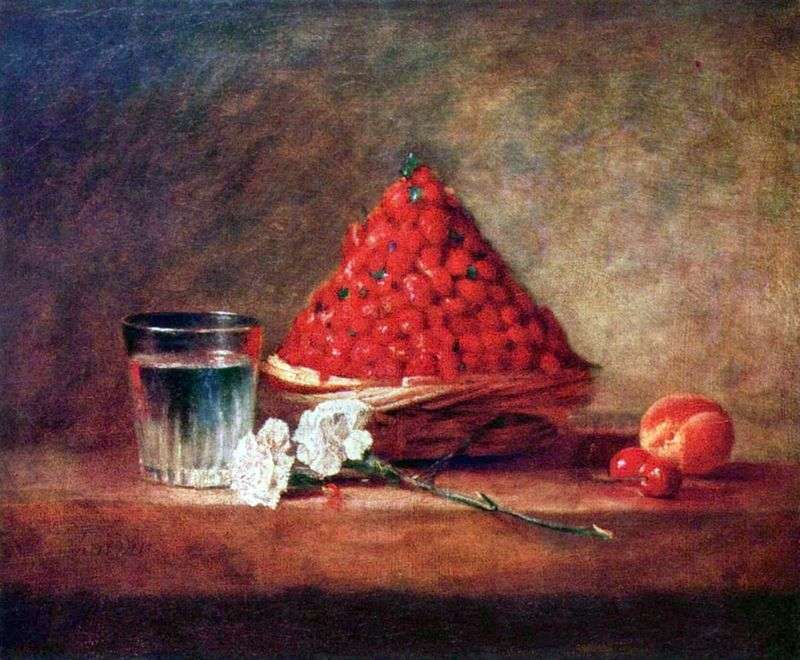

Bodegón con una liebre – Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin Basket with strawberries by Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin

Basket with strawberries by Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin Laundress by Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin

Laundress by Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin A glass of water and a jug by Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin

A glass of water and a jug by Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin Woman pouring water from the tank by Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin

Woman pouring water from the tank by Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin Nature morte au lièvre – Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin

Nature morte au lièvre – Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin