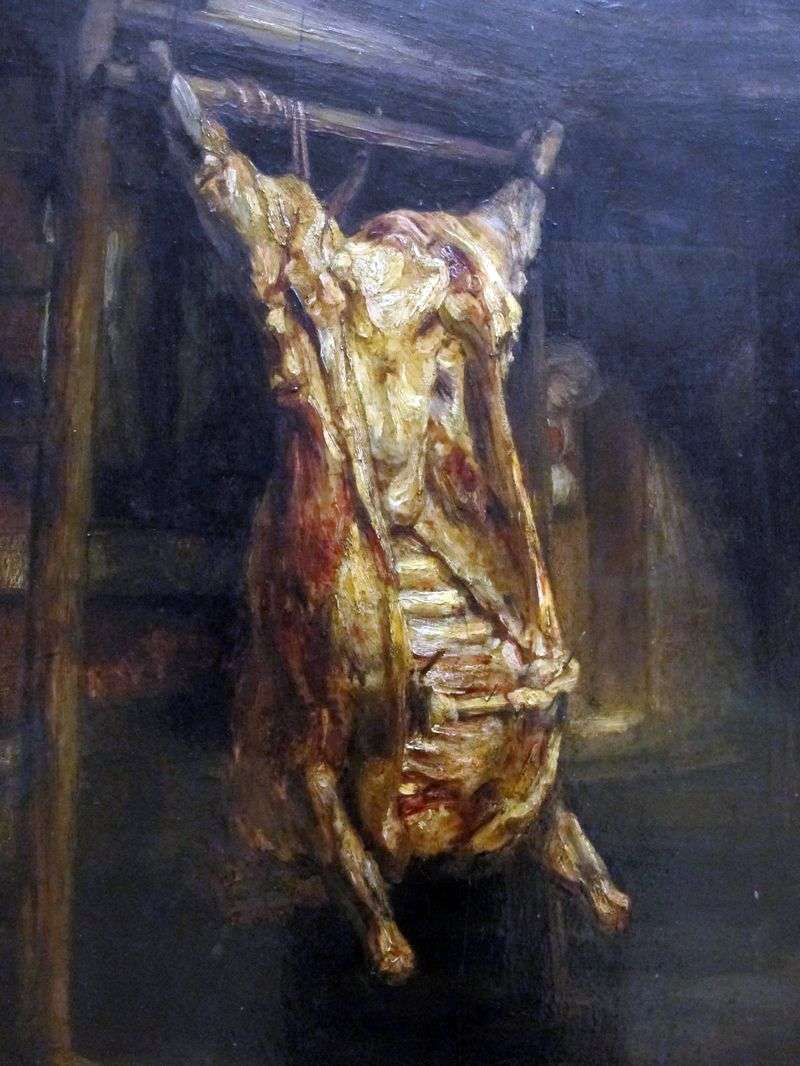

Very often, an unusual motive could have led Rembrandt to carry out bold artistic experiments. An example of one of these experiments can serve as a picture presented from the Paris Louvre entitled “Skinned bull carcass”.

This work, in fact, is a classic still life – in the very, literal sense of the French expression “nature morte”. Sometimes this kind of paintings belong to the category of “vanitas” – works designed to remind man of the frailty of earthly existence, the inevitability of death and the power of God. That is why Rembrandt did not set himself the goal of depicting the “carcass in section” as accurately as possible – in this sense, he even, on the contrary, revives the animal: the artist’s brush returns the life of dead flesh and gives ugly, in general, a picture then a special charm.

The alternation of broad, dense and thin, almost transparent smears in an incomprehensible way “restores” bones, tissues, subcutaneous fat, blood, and even the smell of a more recently living bull. The huge carcass seems truly gigantic in comparison with a small figure of a woman peering through the open door, the appearance of which reduces the sacred and didactic scene to the rank of everyday life. “Skinned bull carcass” will be the object of copying and the subject of their own interpretations of many generations of artists – from Delacroix to Daumier, from Suten to Bacon.

Danae by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

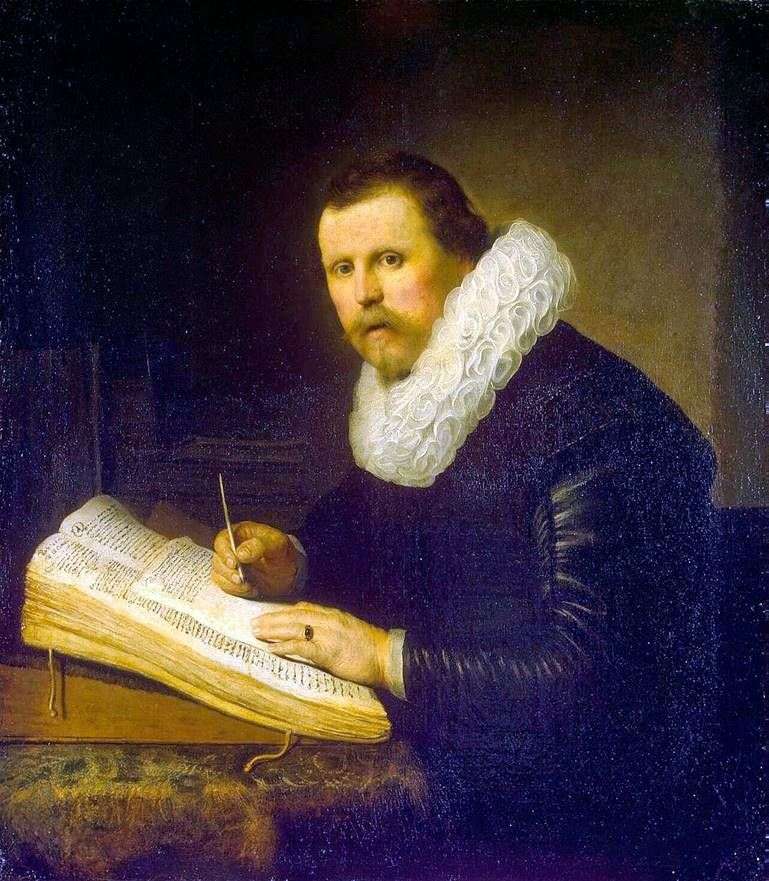

Danae by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Portrait of a Scientist by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

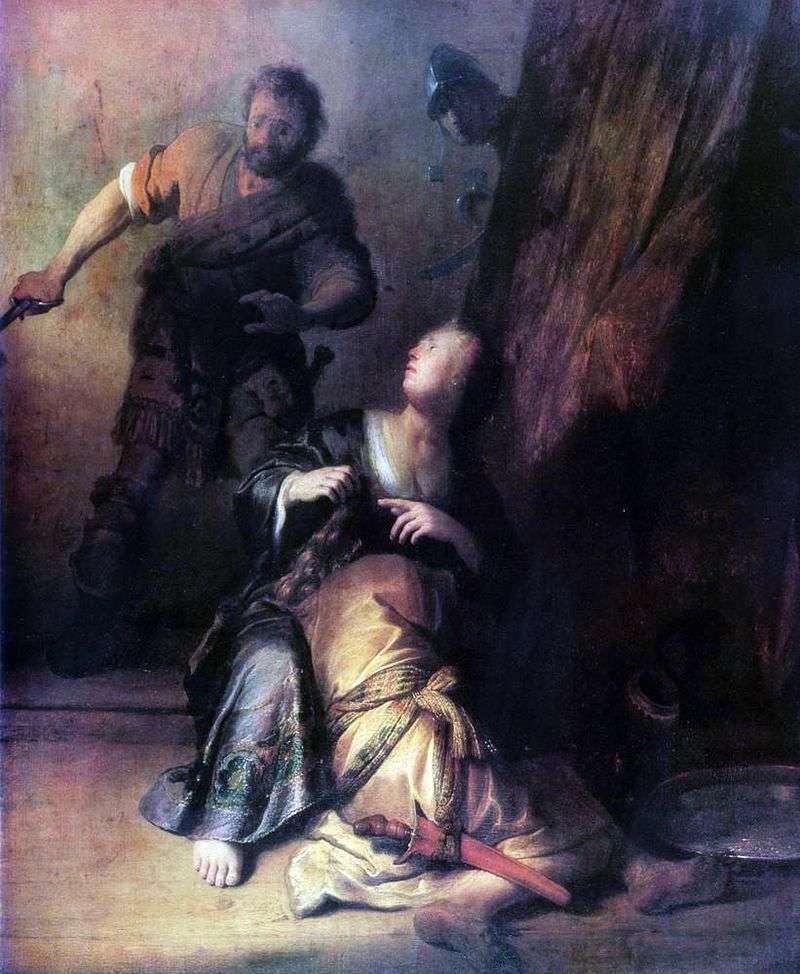

Portrait of a Scientist by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Samson and Delilah by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Samson and Delilah by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Self Portrait at Easel by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Self Portrait at Easel by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Noble Slav by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Noble Slav by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Susanna and the Elders by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Susanna and the Elders by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Batavian Conspiracy by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Batavian Conspiracy by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Hendrickje by the window by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Hendrickje by the window by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine