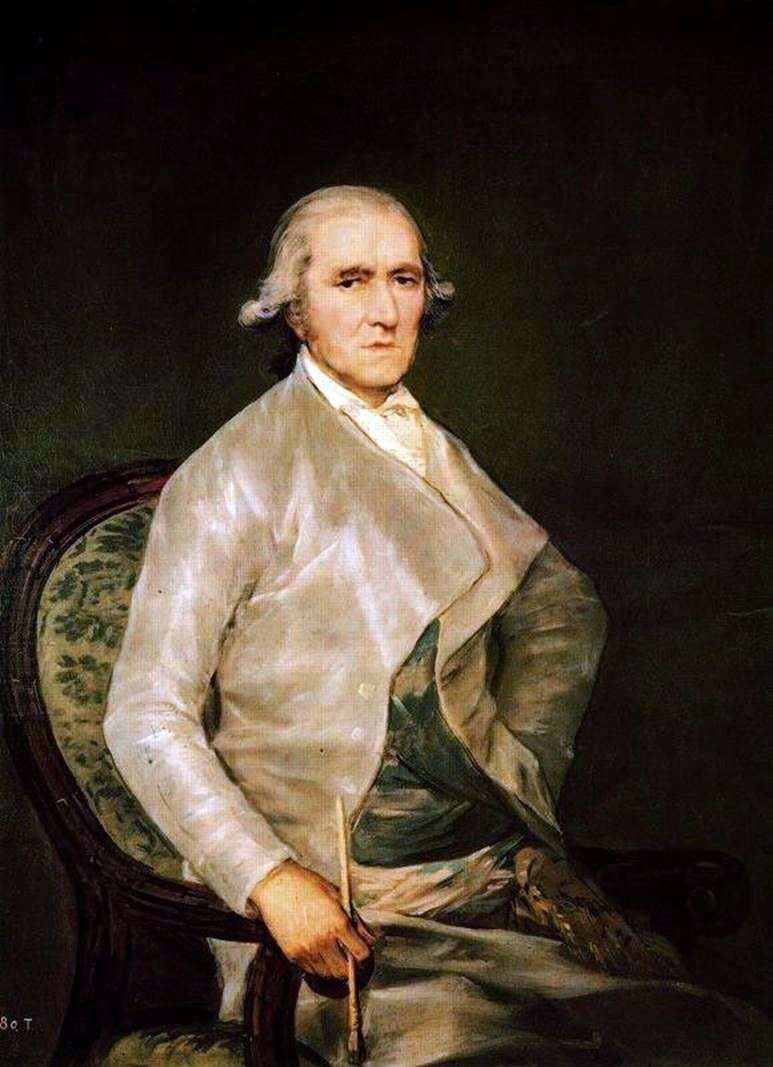

Francisco Bayeu was the brother-in-law of Goya. He, too, was an artist whose young Goya was beginning to learn and who all his life urged him to write on the classical canons of painting, which he himself followed. Bayeux did not understand the obstinate Goya, because he always wanted to write as he imagined his own painting. On this ground between them there were constant frictions, and often the brother was supported by Josef, wife of Goya. And then the disease riveted Bayeu to death. Relatives and friends decided what to do with the unfinished paintings of the artist. Among these paintings was a self-portrait of Bayeux. And then Goya proposed to finish it.

Goya worked with a sense of responsibility and little changed in the already done. Only a bit more gloomy became the eyebrows, a little deeper and wearier lay the folds from the nose to the mouth, the chin protruded slightly more stubbornly, the corners of the mouth sank slightly more fastidiously. He invested in his work and hatred and love, but they did not cloud the cold, bold, incorruptible eye of the artist.

In the end, a portrait of an unfriendly, morbid, elderly gentleman, who had fought his whole life, was finally tired, and of his high position and eternal works, but too conscientious to allow himself to rest.

And yet from the stretcher looked a respectable man who demanded more from life than he was required, and on his own – more than he could give. But the whole picture was filled with a silvery-joyful glow, which Goya’s newly found flickering light gray tone gave. And the silvery lightness overstrained throughout the painting imperiously emphasizes the rigidity of the face and the pedantic sobriety of the hand holding the brush.

The person portrayed in the portrait was unattractive, but the more attractive was the portrait itself.

Portrait of his wife by Francisco de Goya

Portrait of his wife by Francisco de Goya A woman with a fan by Francisco de Goya

A woman with a fan by Francisco de Goya Portrait d’une femme – Francisco de Goya

Portrait d’une femme – Francisco de Goya Retrato de Francisco Bayeux – Francisco de Goya

Retrato de Francisco Bayeux – Francisco de Goya Retrato de una esposa – Francisco de Goya

Retrato de una esposa – Francisco de Goya Portrait of Señora de Sean Bermudez by Francisco de Goya

Portrait of Señora de Sean Bermudez by Francisco de Goya Portrait de Francisco Bayeu – Francisco de Goya

Portrait de Francisco Bayeu – Francisco de Goya Portrait of actress Anthony Sarate by Francisco de Goya

Portrait of actress Anthony Sarate by Francisco de Goya