“Peasant wedding”. This picture of Peter Brueghel was purchased by the Duke Ernst in 1594 in Brussels and after a while appeared in Prague in the famous collection of Rudolph II. The spectator is invited by Bruegel to a lively festival on the occasion of the peasant’s wedding. The picture is full of details: on the left the person fills a pitcher of wine, on the door removed from the hinges they bring to the table a cake, the piper eagerly looks at the food. In everything, Breigel’s ability to catch the rough terrain of the peasants is evident. The drunken, clumsy characters inhabiting Brueghel’s living scenes are the exact opposite of the Italian ideal of refined perfection.

On the life of the peasants. The wedding at Bruegel takes place on the threshing floor of the peasant’s yard. In the XVI century, there were no large tables even in rich houses, they were made during the holiday from the boards. The far right, dressed in a black man, sits on an upside-down tank, the rest on benches made of unplaned boards. On the only chair with a back sitting old man, perhaps a notary invited to enter into a marriage contract. In the foreground, two people serve bowls with porridge, as a door served from the hinges as a tray. The one on the left is the biggest figure on the canvas. Bruegel also identified it in color. Probably, the artist in this way wanted to stabilize the complex composition of the canvas. On the racer, the semi-diagonals of the seated on the front rows converge, and the edges of his apron denote the axis of symmetry of the canvas. On his hat, as well as on the instruments of players on bagpipes, a bundle of ribbons is tied. Such tapes were usually used in those days for garter pants, and their presence on the hat and tools indicated the belonging to a certain group. Young people at that time joined in clicks on the basis of age for joint pastime. In the past, experts tried to interpret Brueghel’s canvas, giving it a religious or allegorical meaning.

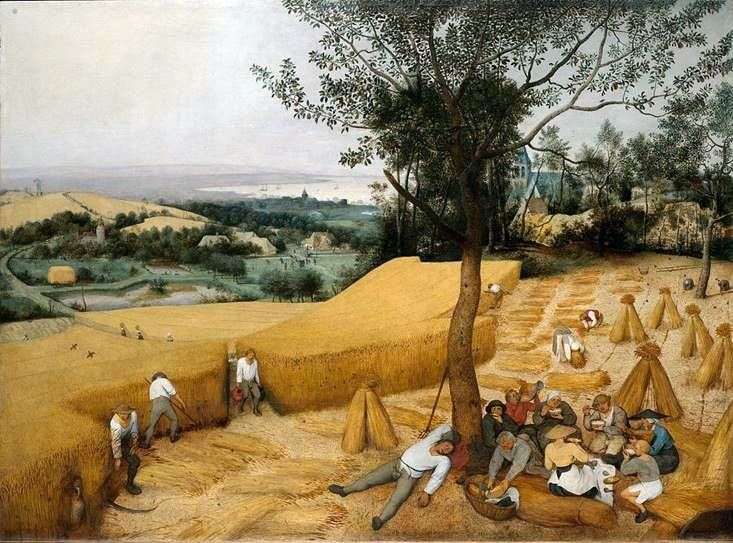

According to one version, the canvas presents “Marriage in Cana of Galilee” during which Jesus turned water into wine, thus allowing the jars to be filled again and again. The other on the canvas depicts the Last Supper. None of the versions was confirmed, it is obvious that the picture is full of realistic details reflecting the reality of the 16th century. Karel van Mander wrote that Bruegel used every opportunity to visit the peasants, whether it was a wedding or any other holiday. Two bundles of ears hang on rakes, the handle of which is deeply stuck into the wheat folded in the barn. The viewer does not immediately notice that the background of the canvas is unmilled wheat. The picture of a full-barn barn in the 16th century meant much more than in today’s time. Cereals served as the basis of food and in the form of cereal and bread were an integral part of any peasant table. Bruegel showed his contemporaries that the people depicted on the canvas will not go hungry for the next 12 months. In those days, famine in Europe was common, fruitful years alternated with lean crops, which led to a sharp rise in grain prices and as a result of this malnutrition, hunger, and epidemics. The lowest prices for grain were immediately after harvest. Most of the cereals were threshed during the period from September to January. In the same months, weddings were usually played. The peasants in the Netherlands lived better in the 16th century than their counterparts in other European countries. They were free, serfdom was abolished, the rule of the Spanish Habsburgs was tolerable. Only in 1567 Philip II sent the Duke of Albu, to dislodge higher taxes and exterminate Protestant heretics. The last years of Bruegel’s life were the last years of the era of prosperity. They were followed by the years of the war for the independence of the Netherlands, years of hardship and suffering.

About poverty. The spoon in the hat of the delivery man indicates that he is poor. After the abolition of serfdom, the number of landless peasants increased substantially. They became seasonal workers who helped in harvesting, harvesting or, as in the canvas, they worked as servants on holidays. As a rule, they lived in huts, they did not have families, because they did not have the means to support it. They constantly wandered from place to place in search of work. Therefore, a spoon in a hat and a bag over his shoulder, the belt of which is visible on the canvas. The round spoon is made of wood. Oval appeared later. At that time the universal tool was a knife. Even the child in the foreground has a knife hanging on the belt. The lord in a black suit is probably the master of the yard. He is a nobleman, or a rich citizen, which is difficult to determine more precisely because the privileges of a nobleman to wear on his side sword at that time no longer adhered. He talks to the monk. At that time, these two estates were closely related to each other. Usually the younger children of the nobility became clergymen, respectively, the church received numerous land allotments and monetary donations. Unlike the bride, the groom on the canvas is not marked by Bruegel so clearly.

Probably it is a person filling jugs, whose place is free at the end of the table. He sits between two men, and the bride between two women. According to custom, they also arranged a wedding dinner, which the groom was not called at all, since the wedding day was considered the day of the bride. The place on which the bride sits is highlighted with a green cloth and a crown hanging over it. The bride makes a strange impression: half-closed eyes, completely immobile, with clasped hands. By custom, the bride on the wedding day was not supposed to do anything. In peasant life, full of daily harassing work, she was allowed one day to peddle. “He came with the bride” – said in a proverb about who was shirking from work. And one more person on the right on the canvas is depicted with linked hands, most likely a city dweller or a nobleman.

About the bride. The bride is depicted on the canvas by Bruegel’s only one of the women with uncovered head. For the last time she shows in the people the luxury of her hair. After marriage, she, like all married women, will cover her head with a handkerchief. On her head is a hoop, the so-called wedding wreath. Its price was precisely defined, as well as how many guests should be invited, how many dishes should be served to the table and how much gifts should the bride cost. The works of Brueghel, based on the observation of real life, are more realistic and humane. According to legend, the artist changed his clothes to take part in noisy peasant gatherings; for which he was nicknamed Bruegel the Peasant. His picturesque technique, however, is by no means rude; neatly applied thin layers of paint perfectly transfuse the saturation and color variety in this picture.

Wedding Dance by Peter Brueghel

Wedding Dance by Peter Brueghel Peasant Dance by Peter Brueghel

Peasant Dance by Peter Brueghel Celebration of the wedding contract by Mikhail Shibanov

Celebration of the wedding contract by Mikhail Shibanov Harvest Summer by Peter Brueghel

Harvest Summer by Peter Brueghel Kids Games by Peter Brueghel

Kids Games by Peter Brueghel The Bird Trap by Peter Brueghel

The Bird Trap by Peter Brueghel Magpie on the Gallows by Peter Brueghel

Magpie on the Gallows by Peter Brueghel The Adoration of the Magi in the Winter Landscape by Peter Brueghel

The Adoration of the Magi in the Winter Landscape by Peter Brueghel