Along with Michelangelo Titian, perhaps, the most grandiose figure of the High Renaissance. His creative life covers almost three quarters of the tragic and turbulent sixteenth century. Titian had occasion to see Italy in the years of the highest rise of her spiritual forces, a deep crisis of the entire Renaissance culture.

But the Venetian artist, who has gone through a long and complicated way of knowing reality, from chanting her sensual beauty to philosophical generalization of her tragic contradictions, carried the ideals of the Renaissance through her whole life, remaining in the later years as a master of this great era.

Portraits of Titian are striking. It seems that the artist simultaneously portrayed a person external and internal. No expression of human feelings or character escaped his charming brush, so there was not a single modern Titian sovereign or nobleman, noble lady or just a man with a great name, from whom the artist would not paint a portrait. As Viktor Lipatov writes, “only breathing was needed to fully revitalize people portrayed in portraits.

Ninety portraits: doji, dukes, emperor, king, dad, fine women, proud and inquisitive men such as Ariosto, Jacopo de Strada, Ippolito Riminaldi, Parma… They were not afraid to pose Titian! Moreover, how did they achieve this honor! “Titian’s portraits of the end of the first and the beginning of the second decade of the 16th century do not reach us, they are already different from the lyrical, full, somewhat vague emotions of his teacher’s portraits-Giorgione, Titian’s heroes are involved in another world-the world of active human deeds. This is a magnificent male portrait.

The entire imaginative structure of this portrait captures the viewer with its concentrated energy. Monolithic and proudly appears before us a powerfully and concisely fashioned figure, looming almost sculptural, plastically assembled silhouette; precious blue-blue color scale, in which a bright-white spot of the shirt and black cloak are interspersed, gets a special power of sound. The face, beautifully crowning the silhouette of the figure, is written still harshly, and at the same time it is full of vivid character. The picture shows, of course, not Ariosto, and not even the “Cavalier of Barbarigo”, about which Vasari wrote, but the pose and look of this unknown overturn all the traditional canons of timid portraiture of Quattrocento.

Portrait of the daughter of Titian Lavinia by Titian Vecellio

Portrait of the daughter of Titian Lavinia by Titian Vecellio Portrait d’un homme (Ariosto) – Titian Vecellio

Portrait d’un homme (Ariosto) – Titian Vecellio Self-portrait by Titian Vecellio

Self-portrait by Titian Vecellio Portrait of a man with a palm branch by Titian Vecellio

Portrait of a man with a palm branch by Titian Vecellio Secular love by Titian Vecellio

Secular love by Titian Vecellio Portrait of Doge Andrea Gritti by Titian Vecellio

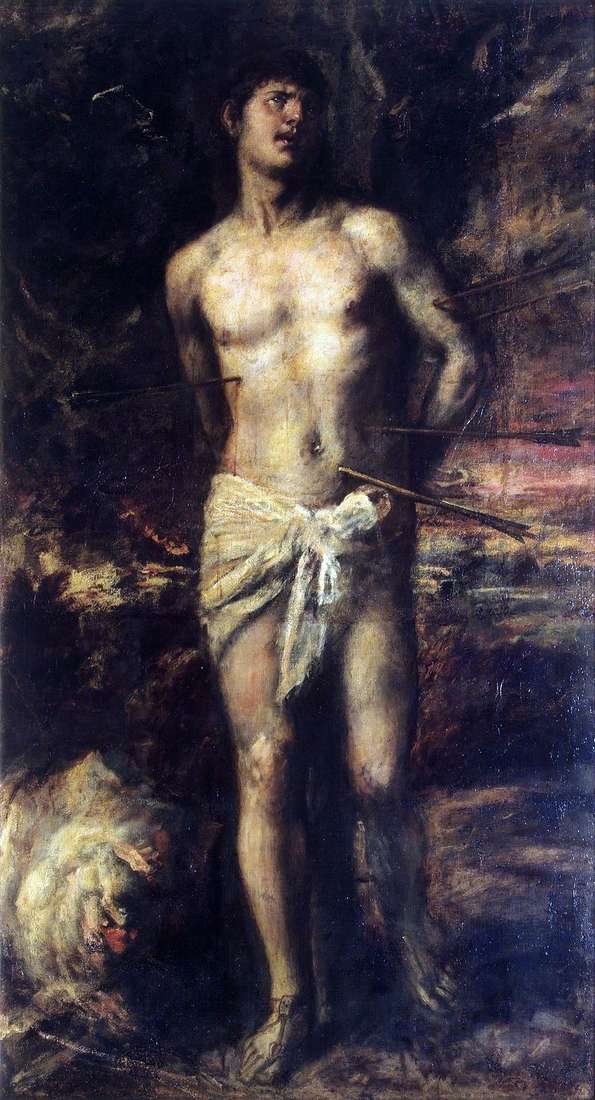

Portrait of Doge Andrea Gritti by Titian Vecellio Saint Sebastian by Titian Vecellio

Saint Sebastian by Titian Vecellio Portrait of Francesco Maria della Rovere by Titian Vecellio

Portrait of Francesco Maria della Rovere by Titian Vecellio