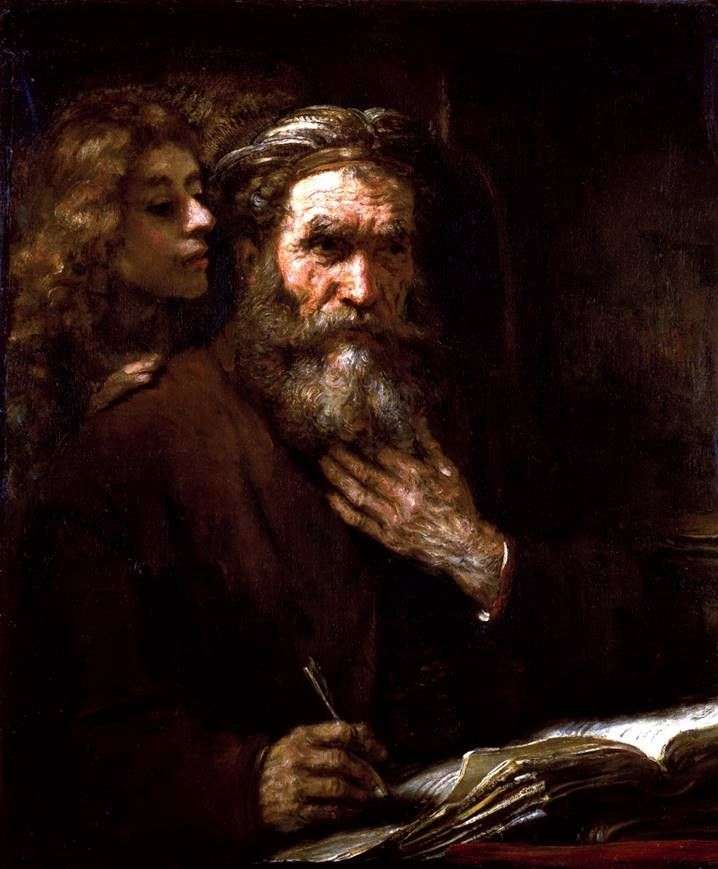

Painting by the Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn “The Evangelist Matthew and the Angel”. The size of the painting is 96 x 81 cm, oil on canvas. A simple, peasant-like coarse man, a staunch advocate for the faith, in the past – a tax collector, here – evangelist Matthew, writes down the words of his master.

Accustomed to physical labor, Matthew holds a feather in his hand, followed by an angel, enlightening his spirit, dictating words to him. Sensually incomprehensible, what we call inspiration, the urge to act, the progressive onslaught, which is the property of all human affairs that transform the world – these qualities were only rarely embodied in such a captivating image: the pure youthful power of creativity, which gives extra-natural-age naturalness to old age.

This picture revealed an extraordinary psychological sense of modernity: this clearly inspired person does not look at an angel or anywhere else, he is immersed in himself and listens to his inner voice, the angel is in himself, not outside of him. In a spectacularly picturesque, contrasting with each other in both images, brush strokes humanize the superhuman – an invisible, but comprehensive, effective, many-sided nature.

The most recent studies suggest Rembrandt’s specific sympathy for the Socianians who were expelled from Poland in the first half of the century, who, relying mainly on the interpretation of the New Testament, in the dispute over Christianity preferred healthy human reason and broke with

This is with the dogma of the Catholic Church and the central position of Calvinism – about the intended saving divine choice. In 1653 followed the merciless defeat of the Socinians by the Calvinist church. Socinian conception of the original mortal human nature of Christ is embodied in the work of Rembrandt when he first departs from the traditional type of Christ, portraying him as a Jew, in accordance with historical accuracy.

Rembrandt combines the humane tolerance with the ideology and activities of this non-church religious group, expressed in the dogmatic-free ethic of his paintings and becoming a reality in his contacts with scholarly clergy of various directions and with “low people” of various nationalities. His strong faith in man includes the moral call of the Sermon on the Mount for an effective, selfless love of neighbor and a deeply conscious dialectic: the first can be the last, the last the first.

Such ideological coincidences, which do not fundamentally contradict the natural-law doctrine of national sovereignty based on the political republican consciousness of natural-law doctrine, than mental analogies to Spinoza or Pascal. Their views for purely temporary reasons could not have a direct impact on Rembrandt, although in some aspects this situation cannot be accepted without hesitation.

Saint Matthew and the Angel by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Saint Matthew and the Angel by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine San Mateo y el ángel – Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

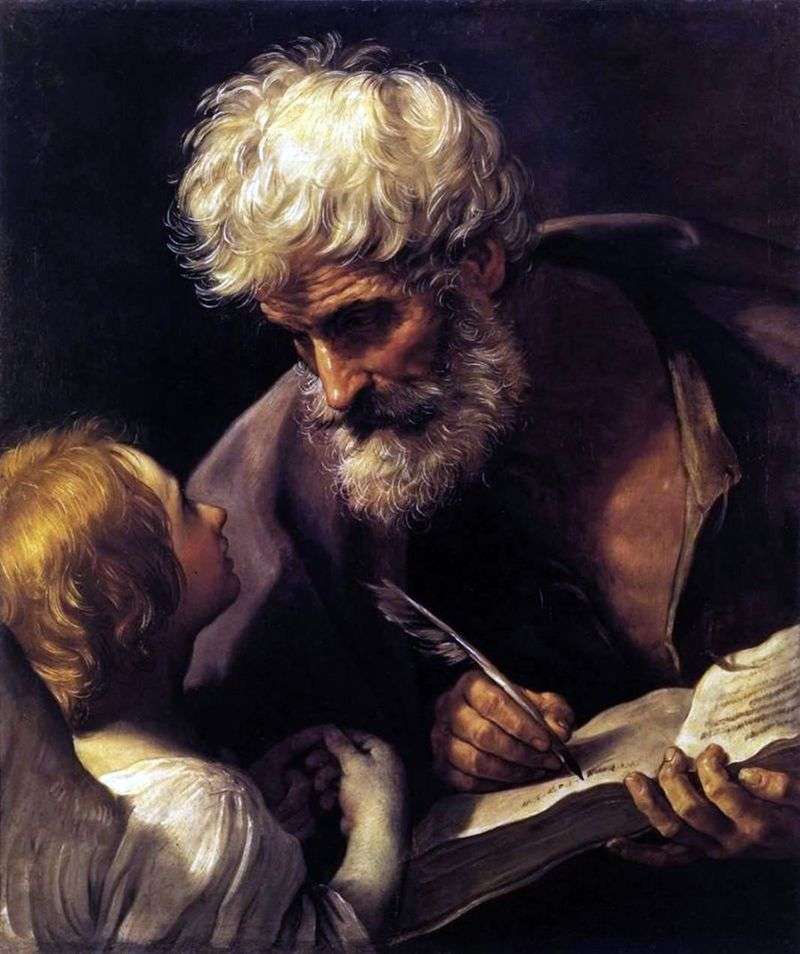

San Mateo y el ángel – Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Saint Matthew and the Angel by Michelangelo Merisi and Caravaggio

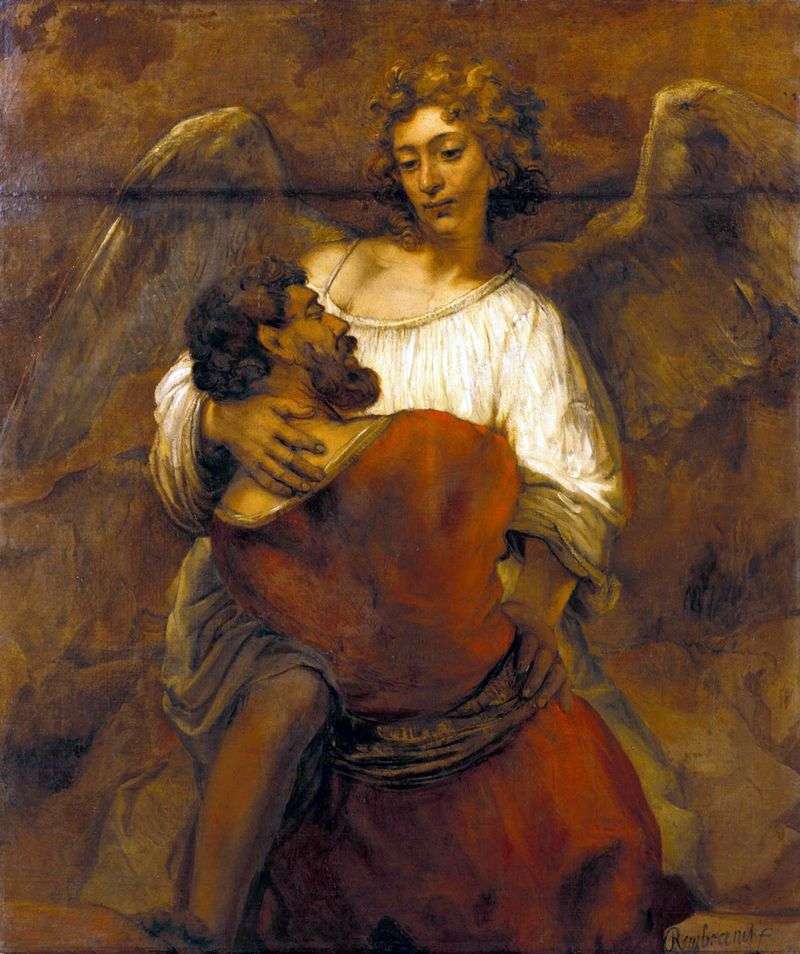

Saint Matthew and the Angel by Michelangelo Merisi and Caravaggio Jacob wrestles with the angel by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Jacob wrestles with the angel by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Apostle Matthew and Angel by Guido Reni

Apostle Matthew and Angel by Guido Reni Jacob wrestling the angel by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Jacob wrestling the angel by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Portrait of an Old Warrior by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Portrait of an Old Warrior by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Jacob lucha con el ángel – Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Jacob lucha con el ángel – Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine