Jesus, surrounded by four tormentors, appears before the viewer with a kind of solemn humility. Two soldiers before the crown crown his head with a thorns crown. Their views are full of cold-blooded responsibility and at the same time, whether true or false sympathy. One even encourages Christ, putting his hand on his shoulder. He, like Judas, is even ready to kiss his victim. But the stick that the warrior holds with his left hand, very soon he will need to deeper to push a thorny thorn in the bosom of the Savior.

A collar with sharp spikes, wrapped around the warrior’s neck on the right, is a mystery to researchers. Such collars were worn on dogs to protect from the attack of wolves. It is also known that in the time of Bosch, one gentleman sentenced to exile on suspicion of complicity in the murder, walked about the streets in a gold collar with spikes to “protect himself from the inhabitants of Ghent.” The collar here is undoubtedly a symbol that Bosch wanted to convey to the viewer.

Below, two Pharisees prepare Christ for the upcoming scourging: one grabs him by the clothes, the other mockingly shakes his hand. On the hood of the Pharisee with a beard, you can see three signs – a star, a crescent moon and something that resembles the letter “A”. Apparently, they should have pointed to his belonging to the Jews. The number “four” – the number of portrayed torturers of Christ – stands out among the symbolic numbers with a special wealth of associations, it is associated with a cross and a square. Four parts of the world; four Seasons; four rivers in Paradise; four evangelists; the four great prophets – Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel; four temperaments: sanguine, choleric, melancholic and phlegmatic.

Many researchers believe that the four wicked faces of the tormentors of Christ are carriers of four temperaments, that is, all varieties of people. Two persons above are considered the embodiment of phlegmatic and melancholic temperament, below – sanguine and choleric.

The impassive Christ is placed in the center of the composition, but the main one is not he, but the triumphant Evil, who took the images of the torturers. Evil seems to Bosch as a natural link in some prescribed order of things. If in the altar triptychs he considers the roots of evil that go back to the past of mankind in the sin of the ancestors, then in the Passion scene he seeks to penetrate into the essence of human nature: indifferent, cruel, thirsting for bloody spectacles, hypocritical and mercenary. Prior to Bosch, art has never risen to such a concreteness of conveying the most complex nuances of the human soul, but it has not gone so deep into its dark depths.

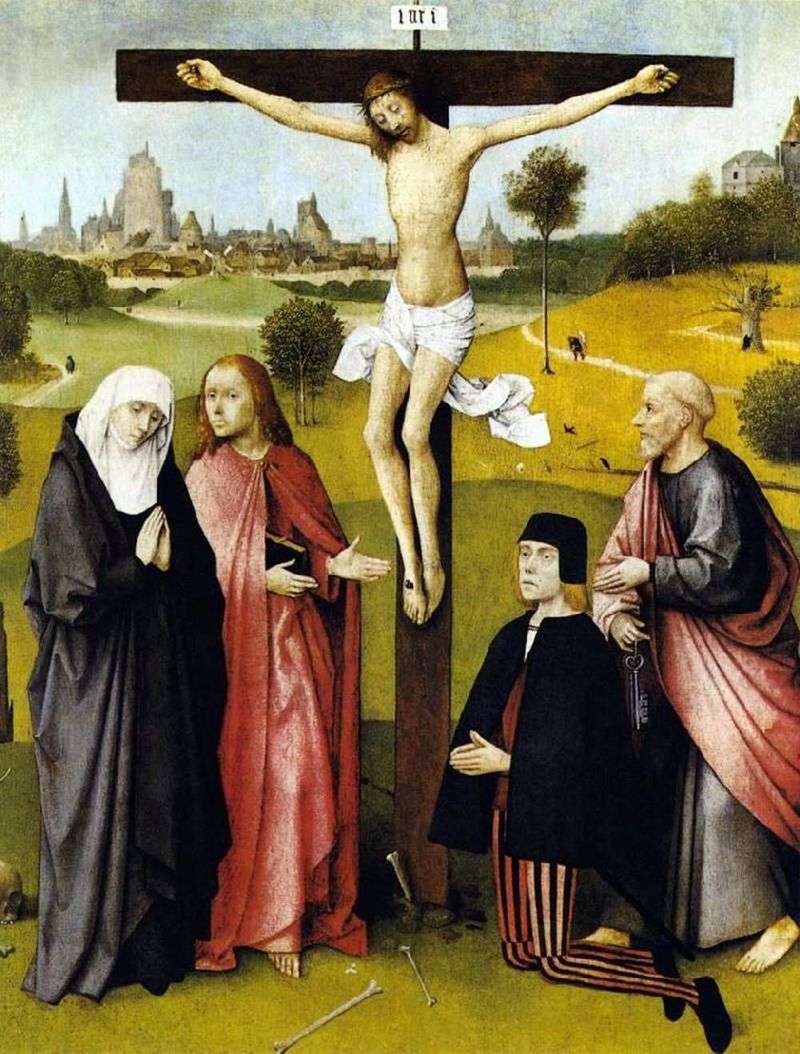

The Crucifixion of Christ by Hieronymus Bosch

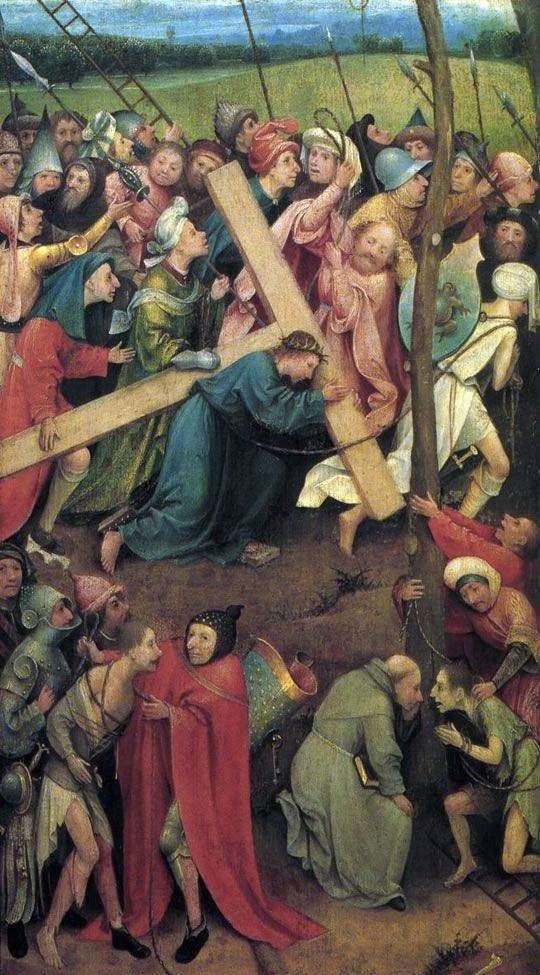

The Crucifixion of Christ by Hieronymus Bosch Carrying the Cross on Calvary by Hieronymus Bosch

Carrying the Cross on Calvary by Hieronymus Bosch The altar of St. Anthony. The central part of the triptych is Hieronymus Bosch

The altar of St. Anthony. The central part of the triptych is Hieronymus Bosch Crowning with thorns by Anthony Van Dyck

Crowning with thorns by Anthony Van Dyck Crowning with thorns by Titian Vecellio

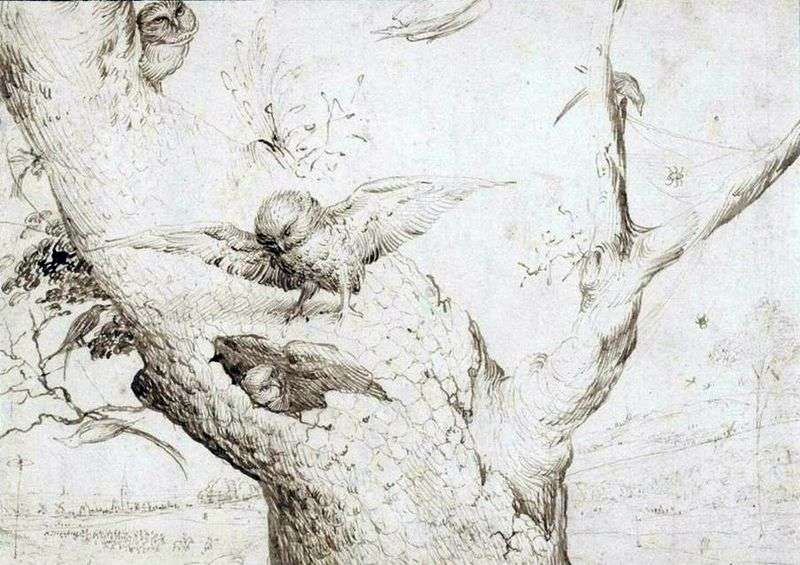

Crowning with thorns by Titian Vecellio Nest of owls by Hieronymus Bosch

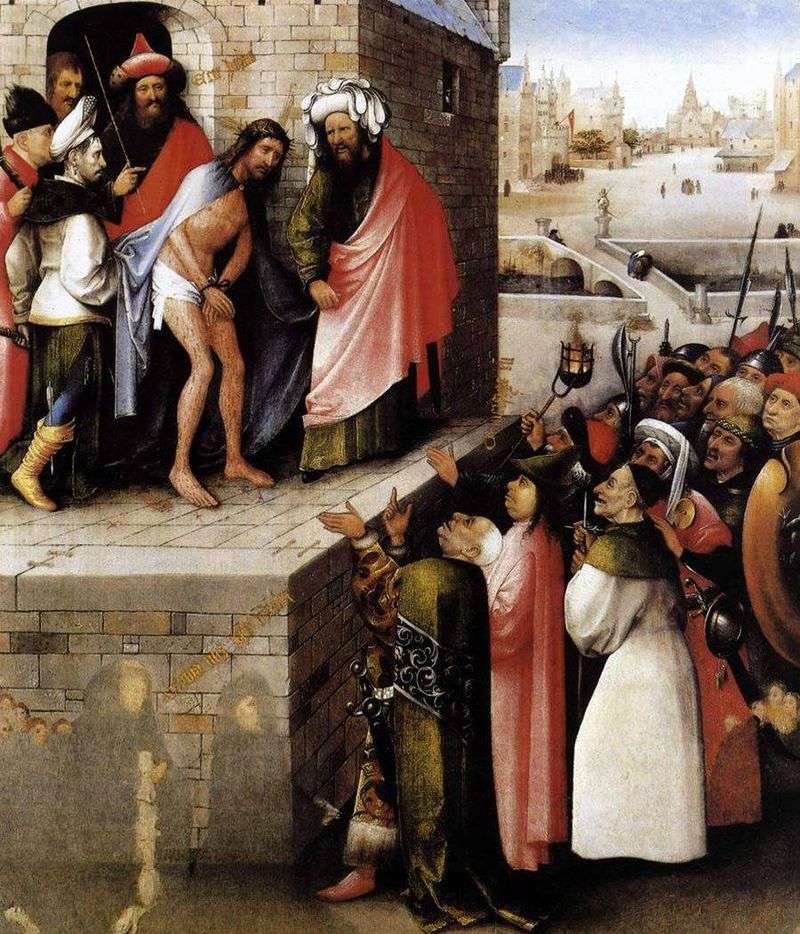

Nest of owls by Hieronymus Bosch Ecce Homo by Hieronymus Bosch

Ecce Homo by Hieronymus Bosch Carrying the cross by Hieronymus Bosch

Carrying the cross by Hieronymus Bosch