Altman is a Soviet avant-garde artist, of those who did not recognize any canons, used a wild mix of genres, for the sake of the goal-the transfer of mood, sensations, events-neglected everyone else.

“Anna Akhmatova” of his brush, despite the fact that it was recognized by all the most unpleasant of her portraits, meanwhile found unmistakable recognition both from relatives and friends. Akhmatova’s daughter writes that although she likes the other portrait of the mother much more, where she looks more affectionate and lyrical, and from Cubism there is no trace, the portrait of Altman better conveys what she was in those years.

The portrait has many acute angles, broken perspective. Akhmatova sits in an armchair, throwing her leg behind her leg, her pointed knee sticks out, a dark blue dress descends to her shoes with stiff folds, her hands are folded on her stomach, the yellow shawl falls off her elbows. The background is extremely generalized, some sharp edges, paradoxically reminiscent of flowers, a gray floor, a wooden bench underfoot. Throughout the pose, according to the manner of writing, a tough, irreconcilable woman with a burning flame inside her emerges.

All of it sticks out with sharp angles – not because that’s what Cubism dictates – but because that’s its essence. Always repressed, forever unreleased, having lost two husbands, Akhmatova is ready to prick sharp corners, repulsing any attack, snapping at any enemy.

However, if in her pose she is apprehensive, almost hostile, her face completely breaks this feeling. Akhmatova looks a little to the side, and on her lips is a strange, gentle smile for such an angular, stern face. As if a carefully guarded flame emerged from inside, as though the sun had glimpsed through the clouds, like something cherished, protected, it seemed possible to appear for a moment and instant, it was immediately masterfully caught and transferred to paper.

Anna Akhmatova – Nathan Altman

Anna Akhmatova – Nathan Altman Anna Akhmatova – Natan Altman

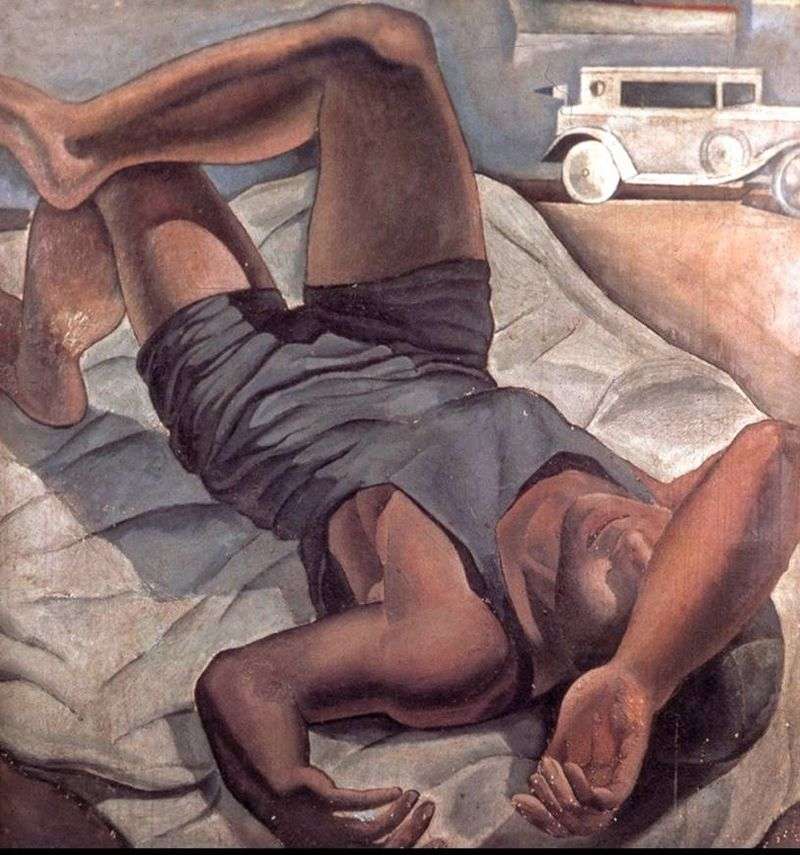

Anna Akhmatova – Natan Altman Bather by Salvador Dali

Bather by Salvador Dali Anna, Viscountess Townshend (Anna Montgomery) by Reynolds Joshua

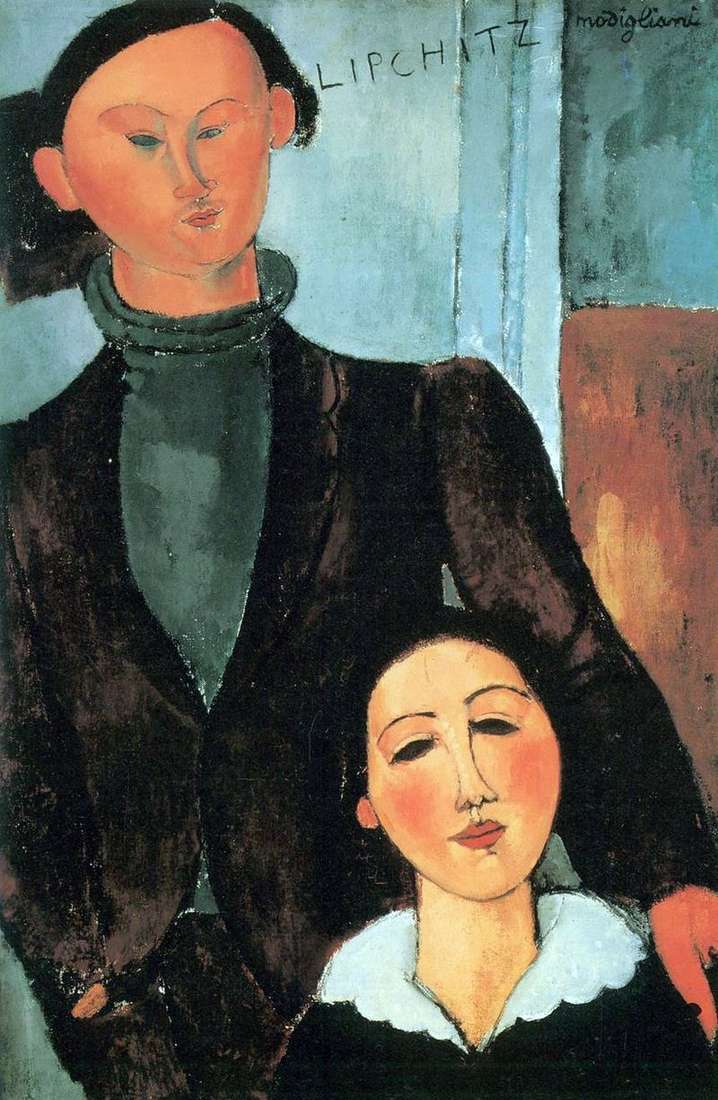

Anna, Viscountess Townshend (Anna Montgomery) by Reynolds Joshua Jacques Lipschitz and his wife Berta by Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques Lipschitz and his wife Berta by Amedeo Modigliani Portrait of Anna Petrovna, daughter of Peter 1 by Ivan Nikitin

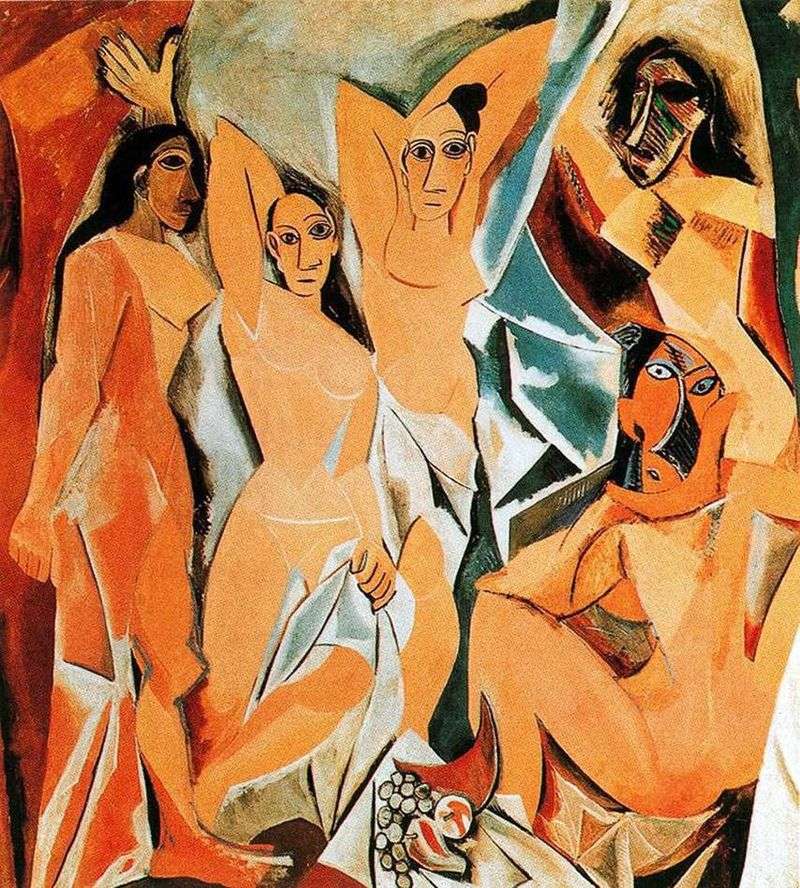

Portrait of Anna Petrovna, daughter of Peter 1 by Ivan Nikitin Avignon Girls by Pablo Picasso

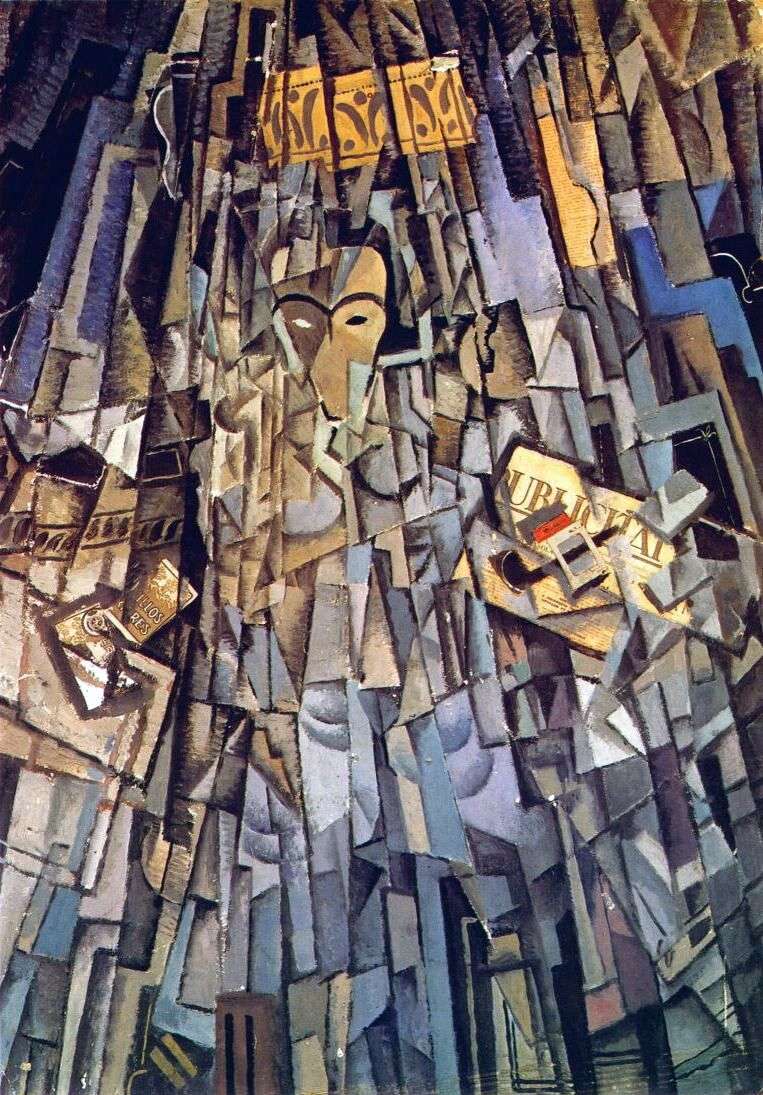

Avignon Girls by Pablo Picasso Cubic Self-Portrait by Salvador Dali

Cubic Self-Portrait by Salvador Dali